West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection

MIKE ROMINE GREW UP in Blennerhasset, West Virginia, not far from DuPont’s Parkersburg plant. Throughout his childhood and young adulthood, Romine was probably exposed through his drinking water to C8, a slippery, soap-like chemical used to make Teflon pans and Stainmaster carpet and hundreds of other products. His home was served by the Lubeck water district, one of six districts near the plant later found to be severely contaminated with the chemical, but his greatest exposure to C8 almost certainly came from working at the DuPont plant, where he was a welding inspector.

MIKE ROMINE GREW UP in Blennerhasset, West Virginia, not far from DuPont’s Parkersburg plant. Throughout his childhood and young adulthood, Romine was probably exposed through his drinking water to C8, a slippery, soap-like chemical used to make Teflon pans and Stainmaster carpet and hundreds of other products. His home was served by the Lubeck water district, one of six districts near the plant later found to be severely contaminated with the chemical, but his greatest exposure to C8 almost certainly came from working at the DuPont plant, where he was a welding inspector.

Romine spent some of his time in the company’s Teflon division, and he particularly remembers taking part in the “Teflon shut down, ” a spring-time ritual. For a few days each year, the company would shut down operations in the plant to prepare for the coming year. Romine helped install new piping. He didn’t know what C8 was at the time, but there was a white powdery substance dusting many of the surfaces in the plant. “It’s on the pipe, on the inside of it, ” said Romine. “You don’t all the time have on gloves. It’s on your coveralls.”

Twelve years ago, when Romine was 58, he was diagnosed with kidney cancer. No one in his family had ever suffered from this rare disease. Surgeons removed the cancerous organ, leaving Romine with reduced kidney function. Now he has to urinate frequently and his doctors have suggested that he change his diet and refrain from running, an activity that had been a regular part of his life before the surgery. Every six months he must return to the doctor to have his remaining kidney checked.

Today, Romine has mixed feelings about DuPont. He worked for the company full-time as a contractor for eight years, and his best friend was employed in one of DuPont’s labs. “In my heart, I felt I was DuPont, ” said Romine, who has enduring respect for the company. “DuPont has really good safety rules, good people, good personnel, ” he said. “I enjoyed working down there.”

Still, for all the good DuPont has done his community as an employer and as a supporter of local organizations and sports teams, Romine is concerned that the company has not been fully honest — especially after a panel of scientists, funded by a class-action settlement, found that kidney cancer and five other diseases had been strongly linked to C8 exposure. “DuPont made me money, ” he said, “but I certainly think now they needed to come clean with whatever happened.”

Still, for all the good DuPont has done his community as an employer and as a supporter of local organizations and sports teams, Romine is concerned that the company has not been fully honest — especially after a panel of scientists, funded by a class-action settlement, found that kidney cancer and five other diseases had been strongly linked to C8 exposure. “DuPont made me money, ” he said, “but I certainly think now they needed to come clean with whatever happened.”

Illustration: Philipp Hubert for The Intercept

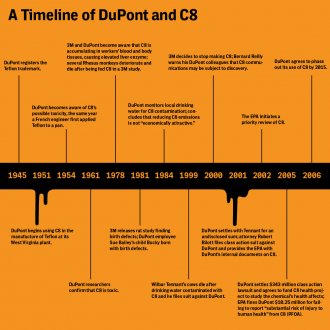

I an attorney named Robert Bilott embarked on an ambitious plan to force DuPont to come clean — to tell what it knew about C8 and, he hoped, eliminate the chemical from the water consumed by Romine and others throughout the country. Bilott sent packages of evidence to the federal Environmental Protection Agency, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, and the Attorney General of the United States, among other regulators. Inside were more than 100 documents he had received through discovery in a lawsuit he had filed in 1999 on behalf of a West Virginia farmer named Wilbur Tennant, whose cows died after being exposed to PFOA, also called C8 because of the eight-carbon chain that makes up its chemical backbone. The documents showed that DuPont, which since the early 1950s had used C8 to manufacture Teflon and other products in its Parkersburg plant, had known for years that C8 posed health dangers and had spread beyond the company’s West Virginia plant into local sources of drinking water.

Bilott even arranged to go to Washington, D.C., to personally present his findings to the EPA. When DuPont attorneys learned about Bilott’s plan, they tried to stop him with a last-minute gag order. They were unsuccessful, however, as Bernard Reilly, one of the company’s in-house lawyers, noted in an email to his son on March 27, 2001:

Bilott even arranged to go to Washington, D.C., to personally present his findings to the EPA. When DuPont attorneys learned about Bilott’s plan, they tried to stop him with a last-minute gag order. They were unsuccessful, however, as Bernard Reilly, one of the company’s in-house lawyers, noted in an email to his son on March 27, 2001:

Court yesterday did not agree to shut up plaintiff lawyer in our Parkersburg situation and today he testifies an EPA hearing and will try to slam us one more time.

Bilott did make his case to the federal regulators and reiterated the request he made in the letter that accompanied his evidence, that the agency regulate C8 under the Toxic Substances Control Act “on the grounds that it ‘may be hazardous to human health and the environment.’”

By some measures, Bilott has in fact been successful in slamming DuPont, but 14 years after he sent his evidence to the EPA, the company has managed to avoid a full reckoning for its actions. And C8, which is in the bloodstream of 99.7 percent of Americans, remains unregulated at the national level.

The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection building in Parkersburg, West Virginia.

Photo: Maddie McGarvey for The Intercept/Investigative Fund

During the five decades in which DuPont used and profited from C8, the company had only infrequently discussed the chemical with environmental authorities, and it kept most of its extensive internal research on the chemical confidential. After Bilott sent out his packages of evidence, however, DuPont’s relationships to government agencies shifted dramatically. Bilott’s revelations had the power to tarnish the company’s reputation and lead to huge legal and cleanup costs, so DuPont focused on weathering the scrutiny of regulators and keeping its name — and profits — unscathed.

Locally, the matter was well in hand. Several regulators at the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection had already shown their allegiance to the company, one of the state’s biggest employers. In October 1996, after the regional office of the EPA began investigating a complaint about one of the company’s landfills, Eli McCoy, the director of the West Virginia DEP, allegedly sent the company a document “to aid DuPont in diffusing any potential enforcement action, ” as Bilott put it in a letter to the EPA. After a few weeks of negotiation, the West Virginia DEP signed off on a consent decree, in exchange for a mere $200, 000 penalty and minor upgrades from DuPont. McCoy then went to work for a consulting firm DuPont hired to help it comply with that agreement.

Locally, the matter was well in hand. Several regulators at the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection had already shown their allegiance to the company, one of the state’s biggest employers. In October 1996, after the regional office of the EPA began investigating a complaint about one of the company’s landfills, Eli McCoy, the director of the West Virginia DEP, allegedly sent the company a document “to aid DuPont in diffusing any potential enforcement action, ” as Bilott put it in a letter to the EPA. After a few weeks of negotiation, the West Virginia DEP signed off on a consent decree, in exchange for a mere $200, 000 penalty and minor upgrades from DuPont. McCoy then went to work for a consulting firm DuPont hired to help it comply with that agreement.

He wasn’t the only regulator who followed the money. As Callie Lyons reported in her 2007 book, Stain-Resistant, Nonstick, Waterproof, and Lethal, three attorneys handling C8 at the West Virginia DEP emerged on the other side of the revolving door as employees of the same local law firm that defended the chemical on behalf of DuPont. Reached for comment, McCoy said that he did not recall details of the matter, noting that he had not worked for the West Virginia DEP for 18 years.

The EPA presented a potentially more challenging situation. The federal agency has the authority to regulate C8 under several laws, including the Toxic Substances Control Act and the Clean Water Act. Through either route, regulation could trigger hefty cleanup costs. In 2002, the EPA initiated what is called a “priority review, ” a critical first step toward regulation, which entails assessing a chemical’s risk to determine whether it should restrict or ban it. The EPA puts a special priority on chemicals that are toxic, persist in the environment, and accumulate in people’s bodies. C8 fit the bill on all three counts.

In response, DuPont assembled a high-powered team that included former EPA officials to oversee its C8 communications with the federal agency. Michael McCabe, a consultant who managed the company’s communications and C8 strategy with the EPA starting in 2003, had served as deputy administrator of the agency until 2001. Linda Fisher, a lawyer who succeeded him in the No. 2 position at the EPA, was also central to DuPont’s C8 campaign. In fact, just over a year after leaving the agency in June 2003, Fisher was already deeply involved in the defense of C8. It surely didn’t hurt that William Reilly, who led the EPA from 1989 to 1993, sat on DuPont’s board of directors.